Article 8(1) of the Federal Constitution upholds the principle that all Malaysians are equal before the law, regardless of gender, background, skin colour, or any form of disability[1].

But how far does this promise stretch for those whose minds work differently from the norm — individuals we now call neurodivergent?

Are they seen, heard, and supported by society? Or are they still labelled “weird”, overlooked and bullied in classrooms, misjudged by professionals, or dismissed simply for not fitting in?

To understand what inclusion really looks like in Malaysia, Wiki Impact spoke to three neurodivergent adults, two living with bipolar disorder, and one with autism, about their lived experiences.

Before we hear their stories, let’s step back: what does it mean to be neurodivergent?

Neurodivergence describes people whose brains function differently in how they think, feel, and interact with the world[2]. These differences were once pathologised as disorders. But today, experts and advocates recognise them as natural variations of the human brain – not flaws, but differences that can bring unique strengths.

The term neurodiversity was first coined in 1998 by Australian sociologist Judy Singer, who argued for a shift in how society viewed autism and other cognitive differences – not as conditions to be cured, but as identities to be accepted[3].

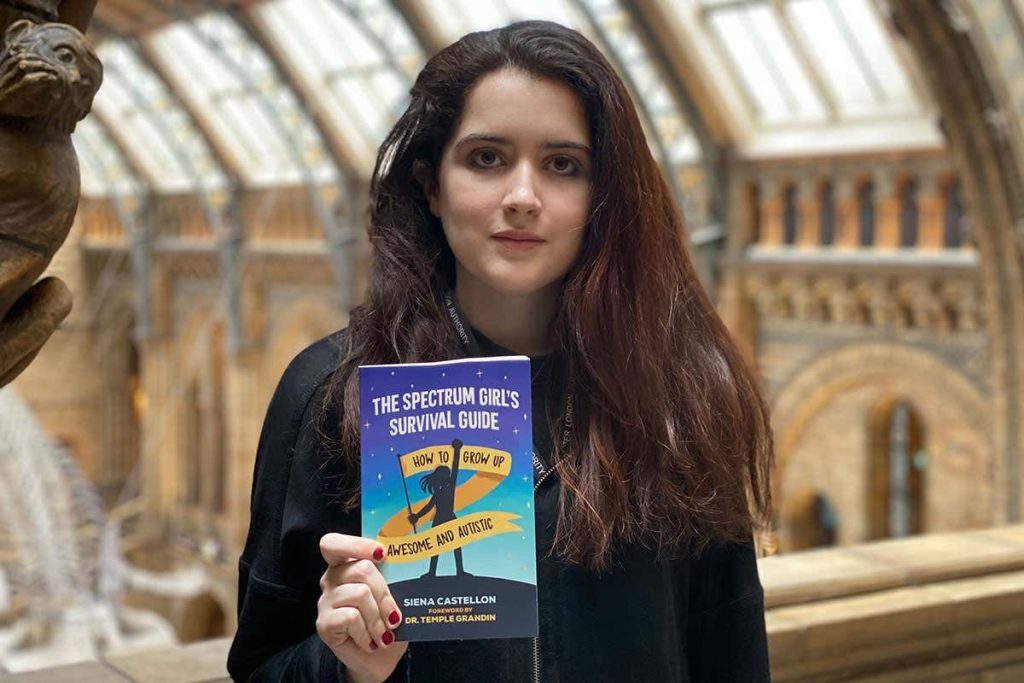

Still, the term took time to gain traction. In Malaysia, it only began entering mainstream conversation around 2018, said Dr. Choy Sook Kuen of Oasis Place. A major push came from British teen Sienna Castellon, who founded Neurodiversity Celebration Week to challenge stereotypes and help schools embrace neurodivergent students[4].

I believe it’s important for neurodivergent students to know that, irrespective of the struggles they face at school, in the right environment, they can be incredibly successful and can still have ambitions and hopes and dreams, just like everyone else. – Sienna Castellon, Founder, Neurodiversity Celebration Week[4]

Now, let’s hear from those navigating life on the spectrum, in their own words.

Too Smart, Too Different: Sahilah vs. The System

At just 11 years old, Sahilah Ain became suicidal, and no one noticed. She had high-functioning depression, a condition where someone experiences deep emotional pain but still appears “normal” and manages daily life.

Fortunately, a school counsellor saw through the mask and referred her to Universiti Malaya Medical Centre (PPUM), where she was diagnosed with Bipolar Mood Disorder Type 1, a condition marked by swings between intense energy and deep depression.

Today, at 28, Sahilah is a cybercriminologist, researcher, and published author. But the road here was anything but smooth, and even now, she continues to struggle.

Speech delays marked her early years. At age three, her sister-in-law took it upon herself to teach her pronunciation and reading. But once she could speak and read fluently, she became a target of bullying and was excluded for being “too smart.”

The teasing followed her into secondary school and university, where she was called a weirdo, mocked for her father’s unique name, and nicknamed “Sahilah gila”.

An early diagnosis gave her access to medical support, but acceptance was another matter, even within her family.

When I suggested applying for an OKU card, my parents rejected the idea. My psychiatrist also advised against it, fearing it would only increase the chances of discrimination. – Sahilah Ain, Cybercriminologist

She soon discovered she didn’t need an OKU card to face discrimination. Once, she applied for a teaching position at a government institution and was offered the job, only to have the offer revoked a month later after she disclosed her bipolar disorder.

Article 8(1) of the Federal Constitution upholds equality, but we have yet to be seen equally. – Sahilah Ain, Cybercriminologist

No Space for Sadness: Ikram’s Quiet Battle

Had he received early intervention after losing a loved one to suicide, things might have turned out differently.

Sollahuddin Ikram, 22, better known as Abg Ikram, didn’t choose to be raised in a family or community where mental health was taboo. Born into a deeply religious and conventional household, he was forced to bury his grief when the only person who truly understood him took her own life. He was just 11 years old.

They pretended like nothing happened. We never talked about it. I was left puzzled, wondering why she did it, and I couldn’t cope with the loss. – Sollahuddin Ikram, Law Student

In the years that followed, Ikram began struggling with concentration, emotional instability, and even heard voices urging him to end his life. But he didn’t seek help. He was underage and terrified that doing so would involve his family, who didn’t believe in mental illness.

It wasn’t until his foundation studies that he was finally referred to a psychiatrist at Mentari Putrajaya. There, he was diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder Type 2, a condition often mistaken for major depression due to its long, overwhelming depressive episodes.

Looking back, Ikram believes his struggles began even before the suicide. Bullied for being soft-spoken and effeminate, he was mocked, harassed, and told to deepen his voice to “sound more masculine.” Art became his escape through dance, theatre, and music.

But when the pandemic hit in 2019, everything unravelled. He lost his sense of direction, college became a blur, and eventually, he attempted suicide. Though he survived, the stigma followed him.

On campus, word spread quickly. Instead of empathy, he was met with suspicion and judgment. People would say things like, “Have you taken your meds today?” or “Can you even handle this task?”

With no support at home, he left. From 2022 until late last year, he found purpose in volunteering with Awas, a suicide prevention initiative and for the first time, a community that understood him.

If people ask me why I moved to Klang Valley, I’d just tell them I came here to study. But deep down, I just wanted to find support. I feel like no one truly understands me… – Sollahuddin Ikram, Law Student

Tired Of Explaining: Adilla’s Battle For Autonomy

It’s no surprise that neurodivergent individuals are often stigmatised and misunderstood, but Adilla has reached her limit. She’s exhausted from having to explain herself over and over again.

Getting diagnosed as an adult is a long, costly process. It took Adilla six clinical psychologists before she finally found one who could assess adults, and the fees were staggering. For many, therapy and diagnosis feel like a luxury, not a lifeline.

Adilla Munir was 28 when she was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome in 2020, now referred to as Level 1 Autism. Even then, it took time for her to fully grasp what her psychologist meant, as autistic individuals often interpret vague language literally.

One day in 2020, I really looked her in the eye – I don’t normally make eye contact, and asked, ‘What do you really mean by High Functioning?’ She looked shocked and said, ‘Autism, Adilla. High Functioning Autism.’ – Adilla Munir, President of Autism Initiatives Malaysia-High (AIM-High)

At the time, Adilla thought her psychiatrist meant high-functioning depression, since she was also going through a difficult period.

Living with chronic illness meant frequent hospital visits, but instead of support, she was often treated as if she were intellectually impaired. Medical professionals assumed she couldn’t make decisions, forcing her to constantly prove her competence: showing her Master’s enrolment, contacting her psychiatric team, or printing letters explaining her diagnosis.

When distressed, she may stim – vocalising or rocking back and forth, behaviours often misinterpreted by those around her.

Now, Adilla is a special education teacher and President of Autism Initiatives Malaysia-High (AIM-High), a professional-supported, autistic-led NGO focused on Level 1 Autism. But her journey here was far from simple.

In school, she often wandered alone during recess, overwhelmed by the noisy dining hall and unsure how social cliques formed. It was in Taekwondo that she finally found a place to belong.

Even in the workplace, disclosure has been a double-edged sword. People either assume autistic individuals are cognitively impaired or genius savants, but most are neither.

When I worked at a place where I had to hide my autism, I burnt out quite badly. Masking, a term autistics use to describe suppressing traits, was something I constantly did. It led me to resign. But I’m lucky my current job allows me to leverage my strengths. – Adilla Munir, President of Autism Initiatives Malaysia-High (AIM-High)

Inclusion or Just Tolerance? How Support Disappears After School

Inclusivity in Malaysia is often praised in policies and posters, but in real life, it feels selective, fragile, and dependent on circumstance.

For Adilla, her university years were a rare pocket of genuine support. She could take exams in a separate room to manage sensory overwhelm, stim in class without judgement, and remain with the same groupmates throughout her studies. This stability helped her thrive. But she quickly learned the workplace was a different world, where behaviours accepted in college became liabilities.

Sahilah’s journey has been just as sobering. From NGOs to corporate roles to government job applications, she’s seen how mental health disclosures, especially in formal settings, can cost opportunities.

There needs to be real improvement in how we accommodate neurodivergent people. Like seriously, you want to create policies for us, but you don’t even include us in the government sector. How can you claim to understand our needs when you have no experience with us? – Sahilah Ain

Her point is clear: representation is impossible if the doors are closed to begin with.

Ikram, still studying, already knows this pattern. After his suicide attempt in college, he wasn’t met with empathy, but with silence, suspicion, and gossip. Even when he kept his diagnosis private, people sensed his difference and kept their distance.

What all three have learned: being “included” often means being tolerated only when your differences are invisible.

Rethinking “Normal”: What Neurodivergent Malaysians Wish You Knew

From their experiences, here’s what they hope Malaysians will finally begin to understand about neurodivergent lives:

#1: To not be hidden but to be seen and heard.

Sahilah wishes society gave neurodivergent individuals the same empathy as those with physical disabilities. They, too, are thriving and doing their best, despite the challenges.

#2: “Mild” doesn’t mean easy.

Adilla stresses that a “Level 1” or “mild” label doesn’t mean life is effortless. Masking is constant, exhausting, and often leads to burnout. What looks “mild” from the outside is a 24/7 effort to adapt.

#3: Acceptance, not fixing.

Ikram emphasises that neurodivergent individuals aren’t broken. They don’t need to be “fixed”, they need to be accepted, accommodated, and understood without judgment.

#4: Thriving is possible with empathy and space.

Ikram points out that many with bipolar, like Mariah Carey, succeed not because their condition is easy, but because they had support. He wishes workplaces offered empathy and space when people are struggling.

#5: Ask us, not about us.

Adilla urges society to talk directly to autistic individuals instead of making decisions on their behalf.

We could be your friend, sibling, or coworker, and you wouldn’t even know, because we’re constantly suppressing who we really are. – Adilla Munir, President of Autism Initiatives Malaysia-High (AIM-High)

#6: Education is key.

Ikram calls for early intervention through mental health education in schools, teaching empathy, emotional skills, and suicide prevention from a young age to prevent more serious struggles later.

These stories aren’t just personal narratives; they’re a challenge to Malaysia. Inclusion can’t just be a slogan. It needs to be lived, practised, and embedded in workplaces, schools, and communities.

Neurodivergent Malaysians are already here, already contributing, part of the fabric of our nation. The real question is whether we’re willing to see them, respect them, and stand alongside them, not just sometimes, but all the time.

Written by Noor Ainun Jariah Noor Harun

Explore our sources:

- A. Hussin. (2023). LETTER | Mandate for change: Fulfilling constitutional equality in all areas. MalaysiaKini. Link

- A. Resnick. (2023). What Does It Mean to Be Neurodivergent?. Verywell Mind. Link

- A.S.F. Lutz. (2023). Asperger’s Syndrome: An Interview with Neurodiversity Originator Judy Singer: A new framework to promote honest discussion about impairment. Psychology Today. Link

- H. Lawrence. (n.d.). Neurodiversity Celebration Week. Twinkle. Link