In 2024, the media was flooded with reports exposing the infamous cult-like organisation, Global Ikhwan Services and Business Holdings (GISBH). Dozens of ex-members came forward to share their stories and experiences after escaping the group.

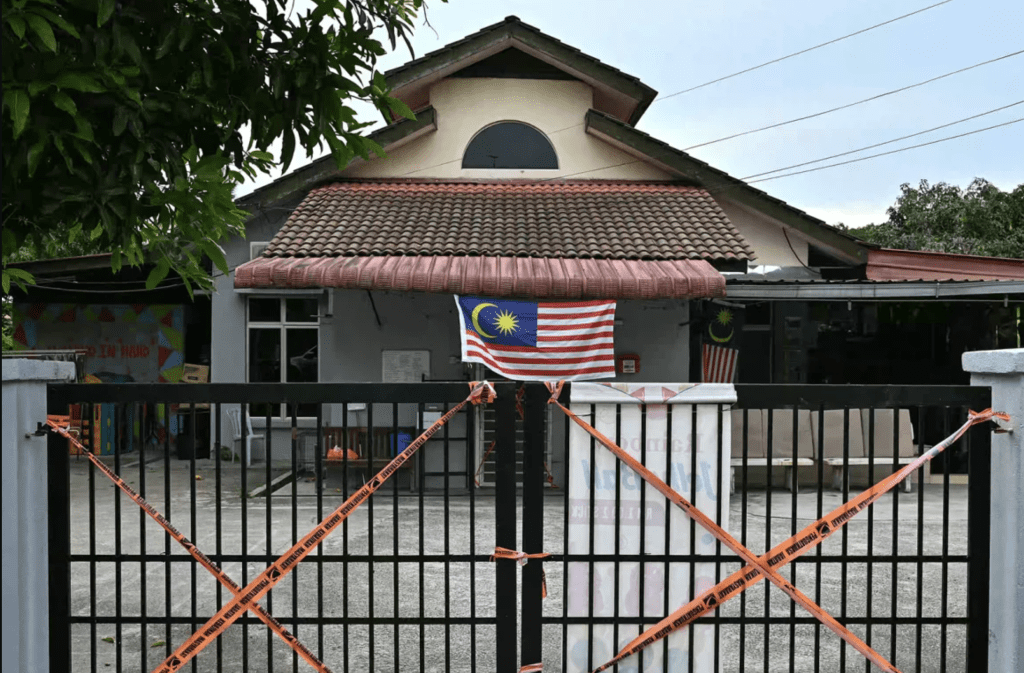

According to Reuters, 22 individuals, including its chief executive, were charged with organised crime, following a wide-ranging probe into GISBH for various offences, including human trafficking, suspected money laundering, and sexual crimes against children. Authorities launched the investigation in September 2024 after rescuing hundreds of children from suspected abuse at care homes run by the firm[1].

What’s troubling is that GISBH is just one of the few cults that have been publicly exposed. Many others remain hidden, blending in seamlessly with society, abusing people in the name of religion under the protection of secrecy and silence.

To understand why cults continue to thrive in Malaysian society and why they often remain unseen, Wiki Impact spoke to a pair of siblings who exited a religious cult they were born into, one that, to this day, has yet to be publicly named or exposed.

Born Into Control

Sara and Wani spent over 15 years inside a cult they were born into. For them, childhood was not about playgrounds or cartoons, but about rituals, restrictions, and fear.

We weren’t allowed to watch TV, read newspapers, or even storybooks. Even talking to each other was discouraged. We had lanyards that said ‘Ingat Allah saja, jangan bercakap’ (Remember Allah only, do not speak). – Wani, ex-cult member

From the beginning, obedience was demanded through silence and social separation, even from their own parents.

The cult’s hold on their family began when their parents, desperate to conceive after a decade of infertility, sought help from a religious figure known as the “Ustaz”.

They gave him money for a cleansing ritual. After that, they had me and my sister. That’s how it started. – Sara, ex-cult member

The family soon became deeply entangled in the Ustaz’s teachings. Though based in Johor, they travelled frequently to Kuala Lumpur for cult gatherings. Members were told the world was ending, and many, including Sara’s parents, emptied their EPF and insurance savings to donate to the Ustaz.

When the apocalypse never arrived, the group shifted focus, first to selling kuih, then to running restaurants, which became a central income stream.

After the Ustaz’s death, a new leader took over, tightening control and turning Sara and Wani’s lives even darker. Sara and Wani’s family relocated permanently to Kuala Lumpur, and the control continued.

How Cults Groom And Control

Mimie Rahman, Managing Director and Registered Counsellor at MINDAKAMI, is a recognised expert in grief, trauma, and suicide, with extensive experience addressing complex emotional issues tied to identity, relationships, and society.

She explained that most cults revolve around a charismatic leader who exploits followers’ need for trust, safety, and belonging.

Often, it begins when someone in a vulnerable season encounters a spiritual group offering warmth and community. The leader seems to have all the answers, and fellow members appear equally transformed. What feels like a safe haven gradually becomes a trap.

At first, there are no strange requests. The group offers hospitality and life advice. Over time, that warmth creates dependency. Once attachment deepens, coercion quietly takes hold. – Mimie Rahman, Managing Director and Registered Counsellor at MINDAKAMI

Financial sacrifice is one of the first demands. Some groups require regular donations; in Sara and Wani’s case, they were told the world was ending and pressured to surrender everything, with promises their debts would vanish. Such giving, Mimie noted, is often driven by guilt and a need to prove loyalty.

Isolation soon follows.

The group might suggest that outsiders, with their worldly concerns, wouldn’t understand this new journey. Slowly but surely, this support system outside the group withers away. – Mimie Rahman, Managing Director and Registered Counsellor at MINDAKAMI

Cults often erase individuality through “deindividuation”, a process where members lose their sense of personal identity. They might begin dressing alike or speaking in coded language understood only within the group.

Sara and Wani experienced this firsthand. After moving to Kuala Lumpur, they were separated from their parents and placed with about 30 children in a communal house. Families were urged to abandon homes and responsibilities for communal living, while children grew up under strict control.

At school, the sisters pretended to fit in, but at home, they were told the outside world was impure and dangerous. They were taught to see themselves as the chosen ones, and their “privileged” path set them apart. This narrative isolated them further and discouraged questioning.

Beyond Belief: When Religion Becomes A Tool For Manipulation

Once members are fully bonded within the group and isolated from the outside world, fear becomes a central tool of control. Members who dared to speak up or question the cult’s rules were often publicly rebuked by the leader and labelled as spiritually weak.

Sara recalled how deeply embedded the hierarchy was, where even a parent’s salvation was said to depend on their child’s obedience to the cult leader.

If we didn’t follow the leader, our parents wouldn’t go to heaven. – Sara, ex-cult member

Every life decision required approval. Elderly members with serious illnesses were denied treatment unless permitted by the leader.

Whether or not they (the elderly or sick) could get help wasn’t up to them, it was his (the leader’s) decision. – Wani, ex-cult member

Two elderly women suffering from breast cancer were forced to keep working despite their condition, under the belief that strength came from Allah and rest was akin to “melayan setan” (giving in to the devil).

If you couldn’t perform, it meant you were weak in faith. – Sara, ex-cult member

Both elderly women died shortly after, never having received proper treatment.

Moreover, Sara experienced this control first-hand when she expressed her desire to further her studies.

They use whatever they give you to control you. If they provide a car, and you don’t obey them, they take it back. – Sara, ex-cult member

When she asked to study, the leader gave an ultimatum: “Choose – go to university or stay here. If you want to study, get out.” With no salary and no financial independence, Sara had no way forward.

Mimie described this as “learned helplessness”, a psychological state where, even if escape is possible, the individual feels incapable of leaving.

Hard To Catch, Harder To Prosecute

Unlike the cults we see in movies, exposing real ones is far more complex. In Sara and Wani’s case, the group they grew up in still operates today, despite repeated encounters with authorities.

A turning point came in 2010, when a parent’s report led to a raid on the children’s house and the cult’s compound. Some children were already at morning prayers; others had just returned from school and were taken for medical checks.

While a few had bruises, most showed no signs of harm, largely because the worst abuse happened after the raid. With little evidence, no charges were brought against the leaders.

Aware they were being watched, the cult shifted tactics. Wani recalled how long prayer sessions were rebranded as “work” at the cult’s restaurant, with labour reframed as worship. Soon after, they opened a roadside stall selling kuih and nasi lemak. Children became unpaid labour, preparing, packing, and selling food daily. All profits went to the leader.

At school, teachers saw warning signs – absent parents, a van full of children claiming to be “cousins.” But the children were well-coached with rehearsed answers, leaving teachers powerless.

A System With Legal Gaps

Prosecuting cults in Malaysia is fraught with gaps, particularly for non-Muslim groups.

According to a report by The Star, only Muslims in Malaysia have a clear legal mechanism to address deviant religious teachings. Islamic deviancy is classified as an offence under state-level syariah enactments, and enforcement falls under the Islamic Development Department (JAKIM)[2].

We have a clear provision of Article 121A in the Federal Constitution, which says that all matters related to religion are dealt with by the state. And Islamic matters will be dealt with according to Islamic rules. – Dr Haezreena Begum Abdul Hamid, Universiti Malaya Criminologist[2]

However, she noted that no equivalent system exists for monitoring religious deviancy in other faiths. Without legal classification or monitoring, some cult-like movements continue to thrive, and those who speak out often resort to informal or public platforms, such as social media or independent reporting[2].

What About Non-Muslim Faiths?

For non-Muslim religions, especially Christianity, introducing legal restrictions is complicated by theological values. Reverend Philip Lok, general secretary of the Council of Churches Malaysia, explained that Christianity places a high value on individual freedom of belief.

This concept of religious freedom is based on our understanding of the Bible and our theological reflections. From our Christian viewpoint, faith in God is required but not coerced. In other words, we believe that a person should be free to choose his or her religious faith. – Reverend Philip Lok, general secretary of the Council of Churches Malaysia[2]

This freedom also extends to differing interpretations of scripture.

In Malaysia, different churches may have different views on certain theological matters, but most of us share the same core doctrinal beliefs. – Reverend Philip Lok, general secretary of the Council of Churches Malaysia[2]

Surviving Escape: The Long Road to Recovery

Despite the extreme abuse, Sara and Wani hesitated to report the cult to authorities, mainly out of fear for their ageing parents.

They’re in their 60s now, and if I report this, they’d be held accountable too, for allowing child abuse and neglect. I don’t want them to go to jail. – Sara, ex-cult member

Like many others who were born into the cult, they had nothing to their names – no money, no assets, not even official identification or bank accounts. Any attempt to save or gain financial independence was impossible due to the cult’s grip over all resources.

While the cult profited from business operations, members never earned a single cent. The leader controlled all resources, making independence impossible.

Even after leaving, freedom didn’t come immediately. They had to unlearn and relearn almost everything, including their understanding of basic human rights.

Sara recalled how her uncle played a pivotal role in helping her transition into the real world.

The first thing he told me was about Malaysian labour laws. He explained how it was illegal for anyone to work like we did – 20 hours a day, seven days a week, no holidays. – Sara, ex-cult member

He showed her official government guidelines, including the Employment Act. For the first time, Sara realised that the life she had known wasn’t normal.

Mimie stressed that recovery is long but begins with safe, supportive spaces where survivors rediscover who they are. Working with trauma-informed professionals is vital, especially those familiar with coercive control and religious manipulation.

That’s why psychoeducation is important. It helps them shift from asking ‘What’s wrong with me?’ to ‘What happened to me?” – Mimie Rahman, Managing Director and Registered Counsellor at MINDAKAMI

Because cults sever outside ties, survivors often feel isolated. Reconnecting with family may be hard, but new hobbies, volunteering, or community groups can offer safe ground to rebuild trust and genuine relationships.

With patience, support, and the right help, survivors can heal and move forward. – Mimie Rahman, Managing Director and Registered Counsellor at MINDAKAMI

Written by Noor Ainun Jariah Noor Harun

Explore our sources:

- M. Leong. (2024). Malaysia charges 22 people linked to Islamic firm GISB with organised crime. Reuters. Link

- U. Ariff. (2024). No laws against deviant teachings in non-Islamic religions?. The Star. Link

Disclaimer: This article aims to raise awareness of coercive practices and is not intended to criticise or generalise any faith community. References to alleged crimes are based on public reports and personal testimonies; Wiki Impact makes no findings of guilt or liability. The views expressed are those of the individuals interviewed. Readers are encouraged to approach this topic with sensitivity and understanding. If you or someone you know may be experiencing manipulation or abuse, please seek professional, legal, or counselling support.